Despite being first proposed 100 years ago, the Equal Rights Amendment has yet to be ratified -- why?

The Equal Rights Amendment was first proposed one hundred years ago by Alice Paul. Passed by the House and the Senate in 1972, the Amendment is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men and women in matters of divorce, property, employment, and other matters. However, the bill still hasn’t been ratified by every state — meaning the fight for equality isn’t over.

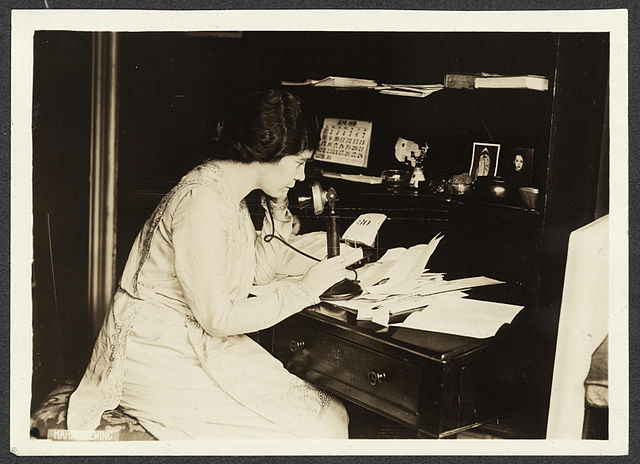

In 1921, the National Woman’s Party announced its plans to promote an amendment to the US Constitution to guarantee equal rights for men and women. The very first Equal Rights Amendment was first proposed in 1923 by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman. Alice further revised the proposed amendment in 1943 to better match the language of the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, the text of which became Section 1 of the Amendment passed by Congress in 1971.

In response to Alice’s 1943 revision, opponents of the ERA proposed an alternate amendment that stated “no distinctions on the basis of sex shall be made except such as are reasonably justified by differences in physical structure, biological differences, or social function.” This alternative was rejected by both pro- and anti-ERA groups.

Interestingly enough, the Equal Rights Amendment was divisive among women of different socioeconomic statuses and even within feminist circles. The concept of “women’s equality” has been debated and largely contested. For Alice Paul and her National Woman’s Party, equality asserted that women should be on equal terms with men in all regards, even if that means sacrificing benefits given to women through protective legislation, such as shorter work hours and no night work or heavy lifting. Opponents of the amendment, such as the Women’s Joint Congressional Committee, believed that the loss of these benefits to women would not be worth the supposed gain to them in equality.

This disagreement signaled a growing tension within the feminist movement of the early 20th century. One approach emphasized the common humanity of women and men, while the other stressed women’s unique experiences and how they were different from men, seeking recognition for specific needs. There was also tension between working-class women who worked to survive, and upper-class women who worked for personal fulfillment.

Although the ERA was introduced in every congressional session between 1921 and 1972, it almost never reached the floor of either the Senate or the House for a vote. Instead, it was usually blocked in committee; except in 1946, when it was defeated in the Senate by a vote of 38 to 35—not receiving the required two-thirds supermajority.

In the 1950s, the ERA was passed with something known as the Hayden rider, named after the rider’s proposer, Arizona senator Carl Hayden. This rider added the sentence “The provisions of this article shall not be construed to impair any rights, benefits, or exemptions now or hereafter conferred by law upon persons of the female sex.” Some felt that adding this rider would make the ERA more appealing and therefore more likely to be ratified, while others felt it entirely defeated the purpose of the amendment.

Throughout its history, the ERA has been opposed by multiple labor and trade unions, which pressured political leaders who identified with labor unions to oppose the amendment. The National Organization for Women, formed in the 1960s after frustration over the government’s lack of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. NOW, by the late 1960s had made multiple legislative and social victories, and in 1970, they picketed the Senate and succeeded in winning a meeting to discuss the ERA. That August, over 20,000 American women went on strike to demand passage of the ERA. While an initial resolution for the ERA ended before being enacted, in 1971 Michigan democrat Martha Griffiths reintroduced the ERA and it was passed in both the House and the Senate.

On March 22, 1972, the ERA was placed before the state legislatures, with a seven-year deadline to acquire ratification by three-fourths (38) of the state legislatures. A majority of states ratified the amendment within a year; however, as the deadline to ratify approached, fewer states ratified the amendment, and several stated even rescinded ratification.

Multiple representatives have proposed legislation to remove the deadline to enact the ERA, but so far this measure hasn’t passed through both the House and the Senate.

What can be done now to enact the ERA? Experts believe there are two paths to achieve federal ratification of the Amendment. One option is through the Constitutional Ratification Process. Article V of the Constitution includes a never-before-used process for ratifying amendments: if requested by two-thirds of the state legislatures, Congress shall call a constitutional convention for proposing amendments. To become part of the Constitution, any amendment proposed by that convention must be ratified by three-fourths of the states through a vote of either the state legislature or a state convention convened for that purpose. This process has no imposed time limit.

The second mode for possibly ratifying the ERA is called the Three-State Strategy. The three-state strategy for ERA ratification was developed following the 1992 ratification of the “Madison Amendment” as the 27th Amendment to the Constitution after a ratification period of 203 years. Proponents argue that the ERA’s ratification period of just over two decades would surely meet the “reasonable” and “sufficiently contemporaneous” standards required by Supreme Court decisions in 1921 and 1939. Precedent regarding a state’s ability to withdraw its ratification by a rescission vote shows that such actions have not been accepted as valid. Thus, supporters argued, the 35 existing ratifications should still be legally viable, and Congress likely has the power to adjust or repeal the previous time limit on the ERA, determine whether state ratifications subsequent to 1982 are valid, and recognize the ERA as part of the Constitution after three more states ratify. This mode is getting closer to realization, with the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment by the state of Nevada in 2017 and by the state of Illinois in 2018, one more state is needed to ratify the ERA to achieve the initial 38 states for federal ratification as determined in 1982.

Even though the ERA was first introduced one hundred years ago, the fight for ratification is far from over. Keeping the dialogue open and utilizing social media is crucial, as is encouraging ratification by additional states.

0 Comments

You can be the first one to leave a comment.